One revenue to rule them all

Why treat "earned" and "contributed" revenue as different streams when they flow from (mostly) the same source?

“Our task is to look at the world and see it whole.”

—E.F. Schumacher, A Guide for the Perplexed

Way back when I started studying Arts Management in graduate school, we talked about two kinds of income for arts nonprofits: earned and unearned. Those labels failed (and still fail) to capture reality on so many levels. They also somehow managed to offend professionals in both lines of work.

Sales and marketing teams felt the “earned” label made their work sound crass and commercial – detached from mission and higher purpose. Development and fundraising teams felt the “unearned” label discounted how much actual work it took to raise contributed funds. (“We earned that contribution,” they would mumble beneath their breath.)

Beyond the bruised egos and bad feelings, the “earned” and “unearned” labels proved to be flawed shorthand for why money actually changed hands. Some ticket buyers were motivated by civic mindedness and support rather than fee-for-service. Some donors were motivated by cost-benefit analysis rather than high ideals.

The more contemporary language of “earned” and “contributed” income softens some of the insult to development staff. But it doesn’t address the larger confusion about whether there are two flows of revenue, or only one.

Back in the early 2000s, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra explored a more coherent view of revenue (Coppock 2008). Moving away from the conventional nonprofit categories – earned revenue, contributed revenue, endowment income – they sorted, instead, by provenance:

Patron-Generated Revenue – any and all income flowing from households, whether as a purchase or a gift.

Community Revenue – grants, gifts, and sponsorships from corporations, foundations, and governments – since they weren’t direct patrons but rather community focused.

Asset-Generated Revenue – income generated by endowment or other assets.

Project Revenue – net revenue from special projects, such as tours or special events.

This reshuffle helped reveal a more coherent approach to household revenue that aligned their production, sales, and development teams toward a shared goal. They concluded:

…if we think of ourselves as being in the concert production business, with ticket revenue as our core revenue, we severely limit potential income. However, if we think of ourselves as being in the patron-development business and think of producing concerts as our mission, new horizons appear (Coppock 2008).

Patron-generated revenue, they realized, derived from three variables: number of households attending, percent of audience households contributing, and average size of household giving. They increased all three by significantly reducing ticket prices (attracting more households while still providing a high-quality experience); speaking early and often about the cost of creating that experience (encouraging a gift mindset among attendees); and developing an organization-wide patron relationship strategy (growing average gifts).

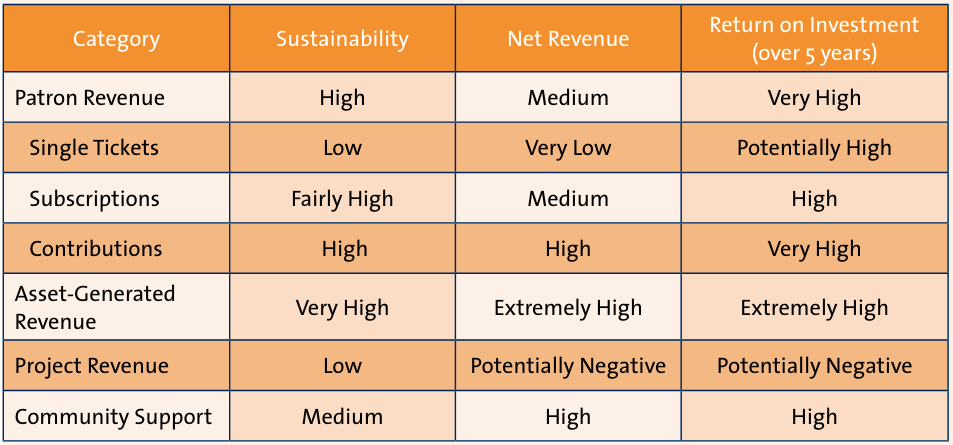

In addition, the new sorting helped them flag and focus on the revenue streams that offered the greatest sustainability, net revenue, and return on investment over time (see chart).

There is value, of course, in breaking things down to understand their constituent parts. Sales and gifts do have many unique attributes and challenges that are worthy of separate attention. But it’s important not to lose sight of the forest for the trees, and always to honor the river that runs through it.

p.s. For more on patron-generated revenue as an essential metric, watch this short video from TRG Arts.

From the ArtsManaged Field Guide

Function of the Week: Sales

Sales involves designing, deriving, and capturing inbound revenue from goods, services, or access.

Framework of the Week: Recency, Frequency, Monetary Value (RFM)

Recency, Frequency, Monetary Value (RFM) is a simple but powerful framework for segmenting a customer, audience, or donor list according to transaction patterns – focusing on how long ago they were active (recency), how often they were active (frequency), and how much they spent or contributed in total (monetary value).

Sources

Photo by Alexander Grey on pexels

Coppock, Bruce. “Radical Revenue: A New Business Model Challenges Conventional Industry Thinking.” Symphony Magazine, 2008.