The job description multiverse

"So, what do you do?" is a trickier question than you might imagine (or prescribe, or disclose, or actually demonstrate).

“It is perfectly true, as philosophers say, that life must be understood backwards. But they forget the other proposition, that it must be lived forwards.”

—Søren Kierkegaard

“Other duties as assigned” is a magical phrase in many job descriptions, as it captures a universe of uncertainty in just four words. Even when the phrase is missing, we all know it’s implicitly there, since no list of duties can possibly capture the complex and contextual reality of anyone’s actual work.

This can be a problem when you want to recruit, hire, support, and evaluate members of your team. All of those activities require some fair and shared understanding of capacity or performance. And yet no single description will ever be complete.

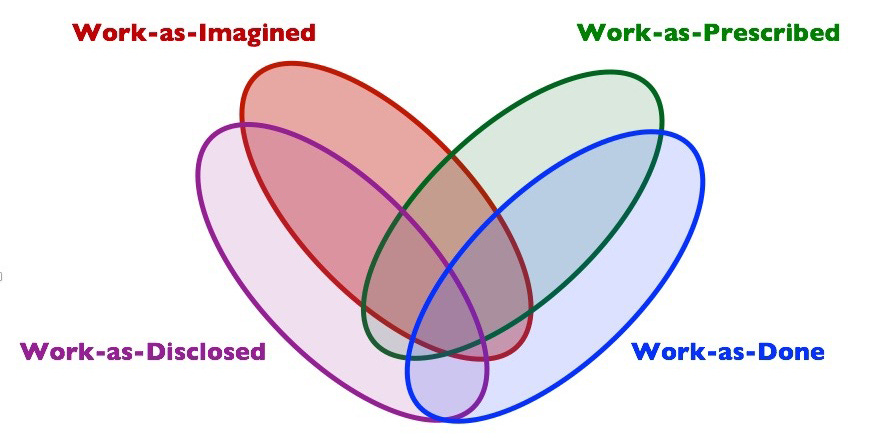

Rather than a single, flawed description of a job, psychologist and human factors specialist Steven Shorrock suggests that there are four overlapping varieties of human work that each have their flaws and features (2016):

Work-as-Imagined is the bundle of beliefs about the job, both about what people currently do, or what they (or we) might do in a future scenario. “To a greater or lesser extent, all of these imaginations – or mental models – will be wrong; our imagination of others’ work is a gross simplification, is incomplete, and is also fundamentally incorrect in various ways, depending partly on the differences in work and context between the imaginer and the imagined.”

Work-as-Prescribed is the formal specification of the work appearing in laws, regulations, rules, procedures, checklists, standards, job descriptions, or management systems. This is the official measure used for performance evaluation, but also can never capture the full context or variety of the work.

Work-as-Disclosed “is what we say or write about work, and how we talk or write about it.” It is the job we describe when we are aware of our audience, or attentive to the consequence of what we say. For example, when a surgeon describes a procedure to a patient, they simplify to ensure understanding. When a team member describes their job to a supervisor or peer, they may “spin” the description to defend their position.

Work-as-Done “is actual activity – what people do. It is characterised by patterns of activity to achieve a particular purpose in a particular context.” That doesn’t make it the right thing to do, just the thing that is done. This category is often ignored because it is difficult to observe and capture – especially since any observation changes behavior.

So what’s a poor manager to do when no description of a job can be complete, accurate, or context-independent? First, get over it. Second, focus on the outcomes of the work as indicators of performance, rather than the specific tasks. When the actions, themselves, have to be specified – for compliance or consistency or training – define them as clearly and cleanly as you can, but also hold those definitions lightly and be open to variation or change.

Third, discuss and identify the gaps between these four varieties of human work in your own organization (Dekker 2017) – what’s the difference between a job as imagined, as prescribed, as disclosed, and as done? And how can your whole team work collaboratively to reduce those gaps?

And finally, honor the reality that you and your co-workers are humans, and therefore subjective, situated, and social beings. That’s a feature not a flaw, even though it can be inconvenient to predictable and efficient operations.

From the ArtsManaged Field Guide

Function of the Week: People Operations

People Operations involves designing and driving systems and practices that attract, engage, retain, and develop people within the enterprise (also called human resources).

Framework of the Week: Personal Projects

The Personal Projects framework was developed by psychology scholar Brian R. Little to interrogate the way people understand and organize their actions in the world. He defined personal projects as "extended sets of personally salient action in context."

Photo by Adam Sherez on Unsplash

Sources

Dekker, Sidney. “Resilience Engineering: Chronicling the Emergence of Confused Consensus.” In Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts, edited by David D. Woods, Nancy Leveson, and Erik Hollnagel, 1st edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2017.

Shorrock, Steven. “The Varieties of Human Work.” Humanistic Systems, May 12, 2016.